Helicopter operations can be integrated safely in the vicinity of largeairports, including cases where heliports are within the Aerodrome Traffic Zone (ATZ) of large commercial airports. This study examines cases of such heliports, how air traffic control (ATC) manages such operations, the relevant regulatory framework (ICAO and EASA), real-life case studies, safety best practices, and how these can be applied to Athens International Airport (LGAV).

The evidence indicates that helicopter traffic could be managed within an airport’s ATZ without compromising safety and efficiency, as long as there is adherence to the appropriate procedure and legislation.

1. Identifying Heliports close or Within ATZ of Major Airports

Definition of ATZ: An Aerodrome Traffic Zone (ATZ) is defined as “an airspace of defined dimensions established around an aerodrome for the protection of aerodrome traffic”

Typically in Europe, an ATZ extends from the surface up to 2,000 feet above ground level and has a radius of 2–2.5 NM around the aerodrome’s reference point (depending on runway length)

Any heliport or helipad located within about 3 NM of a major airport would generally lie inside that airport’s ATZ or control zone.

2. Case studies of Heliports Near Major Airports:

There are several instances in Europe where heliports operate within ATZ of large airports (more than 80 close to domestic airports):

- London Heathrow & Local Heliports (UK): Heathrow Airport (EGLL) is one of the world’s busiest airports, yet its control zone accommodates several nearby off-airport helicopter landing sites. The London Heathrow Crowne Plaza Heliport (1 NM from the airport) operates with strict procedures: pilots must coordinate with Heathrow Tower/Radar for arrivals and departures. Typically, a helicopter departing this pad will be instructed to remain well clear of runway approach paths (often by staying north of the airport) and below a certain altitude until leaving the zone. Heathrow ATC may hold the helicopter if necessary until a gap between arriving jets, then clear it across the approach path at low altitude. Similarly, inbound helicopters are sequenced to enter after departing traffic or between landing gaps. The successful use of this heliport demonstrates that even within the Heathrow ATZ, helicopter operations can be managed safely. During the Royal Ascot event, up to 400 helicopter movements occur over a few days via the Ascot heliport just west of Heathrow’s airspace, all handled through Heathrow’s CTR with predetermined routes

- Monaco Heliport (Monaco): Located in the Fontvieille district of Monaco, approximately 1.2 nautical miles from Nice Côte d’Azur Airport (LFMN). Provides helicopter transfers between Monaco and Nice, catering to both private and commercial clients. Despite being in a different country, its close proximity to Nice Airport necessitates coordinated airspace management.

- Zingem Heliport (Belgium): Near Zingem, East Flanders, Belgium, approximately 2.8 nautical miles from Kortrijk-Wevelgem International Airport (EBKT). A private heliport serving local helicopter operations. Its proximity to Kortrijk-Wevelgem Airport requires coordination with the airport’s air traffic services.

- Reninge Heliport (Belgium): Near Reninge, West Flanders, Belgium, approximately 2.5 nautical miles from Ostend-Bruges International Airport (EBOS). Operated by Restaurant ‘t Convent, serving private helicopter operations. Close proximity to Ostend-Bruges Airport necessitates coordination with air traffic control.

- Paris Issy-les-Moulineaux Heliport (France): The Paris Heliport at Issy is a busy facility only a few kilometers from downtown Paris. While not immediately next to Charles-de-Gaulle or Orly, it sits under Paris’s Class A/C terminal airspace. All flights to or from Issy are coordinated with Paris ATC. Departure routes from Issy are designed to avoid overflying central Paris (both for noise and airspace restrictions). Helicopters typically must climb no higher than a few hundred meters and exit via specific reporting points on the edge of the city before being allowed to climb or proceed on course. Paris’s airspace is complex (with some sectors off-limits to VFR), yet Issy Heliport has operated for decades with a strong safety record. One reason is strict procedural compliance – helicopter pilots inbound to Issy must hold at defined points if clearance into the zone is delayed, ensuring they don’t conflict with airliners overhead. Issy handles a range of traffic: corporate shuttles, sightseeing tours, police and EMS helicopters. Its continued operation demonstrates that a heliport can thrive in the shadow of major international airports given proper airspace management and regulatory support.

- Nice Côte d’Azur & Monaco Heliport (France/Monaco): Nice Airport (LFMN) handles significant airline traffic on the French Riviera. About 7 NM to its northeast lies Monaco’s coastal heliport. There is a well-established scheduled helicopter shuttle service between Nice and Monaco, with more than 50 flights per day in peak season. These helicopters depart Monaco, enter Nice’s controlled zone, and land at Nice Airport’s helicopter area (and vice versa). The procedure is very structured: departures from Monaco immediately turn out over the Mediterranean Sea and stay offshore, remaining clear of the approach paths to Nice’s runwaysThey fly at 500–1000 ft along the coast. Nice Tower/Approach sequences them among the fixed-wing traffic, often by issuing speed and altitude restrictions. For example, a helicopter might be cleared to approach the airport following the coastline until abeam the runway, and only then cross in to land once an arriving Airbus has touched down. Noise abatement and safety considerations keep the helicopters mostly over water. This arrangement has been successful for decades, including during high-traffic events (e.g. Monaco Grand Prix) when helicopter movements surge. It highlights how separate routings (over water) and tight ATC control enable safe operations within a busy airport’s environs.

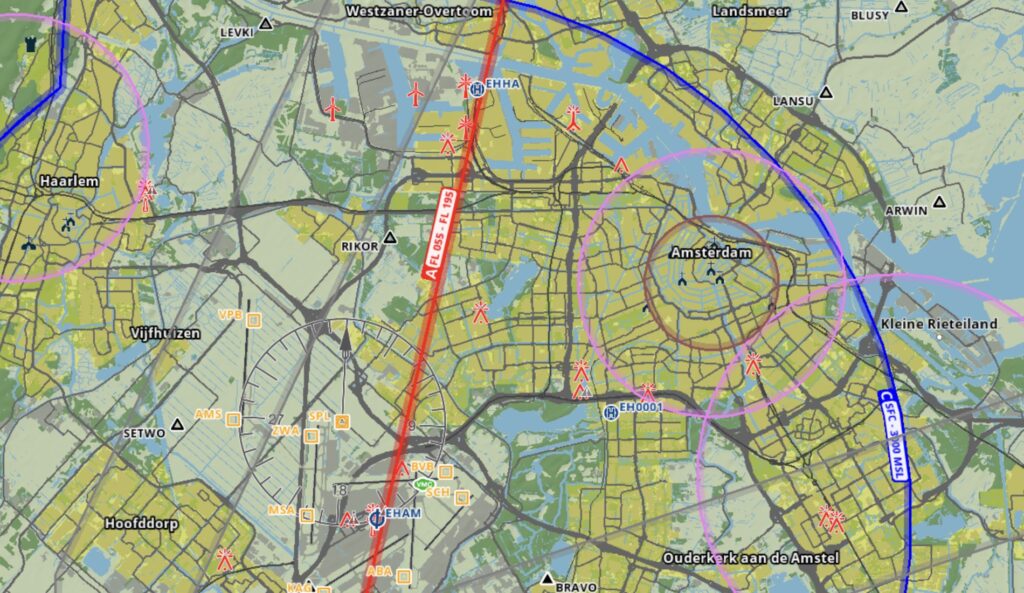

- Amsterdam Heliport (ICAO: EHHA): Amsterdam Heliport (ICAO: EHHA) is a modern heliport situated in the northwest of Amsterdam about 2 Nm from Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, within the Westpoort harbour area. Established in 2005, it primarily caters to VIP transport and aerial work operations. Heli Holland, the largest helicopter operator in the Netherlands, utilizes Amsterdam Heliport as one of its main bases. The company offers services such as VIP transport, offshore transport, flight training, aerial photography, medical flights, freight transport, and aerial inspections

Each of these case studies reinforces the same point: with carefully designed procedures and proactive ATC control, helicopter operations in the proximity of major airports are being conducted safely and efficiently. They serve as a proof of concept that the Greek HCAA can look to when evaluating similar proposals for Athens. Key themes from these examples include the use of segregated routes, altitude separation, timing (slotting helicopters between gaps in traffic), and close communication between pilot and controller at all times.

3. ATC Management of Helicopter Operations from Heliports in an ATZ.

ATC Coordination and Clearances: Helicopter flights operating within a controlled zone or ATZ of a major airport are always subject to ATC clearance. For example, “all helicopter flights in the London (Heathrow) and London City Control Zones (CTRs) are subject to an ATC clearance due to the classification of airspace”

Pilots must establish two-way communication with the airport tower or approach control and obtain a clearance before entering the ATZ or taking off within it. ATC instructions ensure that helicopters integrate safely with ongoing arrivals and departures.

Use of Dedicated Helicopter Routes: A common method to manage heliport traffic is the use of published VFR helicopter routes that avoid the primary fixed-wing traffic streams. In London’s CTR, for instance, predetermined routes (Helicopter Lanes H1–H10) have been established across the city’s controlled airspace to “assist with the integration of helicopter flights into the airspace”

These routes keep helicopters over less populated areas (e.g. following the River Thames in London or the coastline near Nice) and at altitudes that minimize conflict with airliners. ATC may instruct helicopters to follow these routes, or when traffic permits, may authorize more direct routings across the zone.

Traffic Pattern and Altitude Management: Helicopters generally do not fly in the same traffic circuit as fixed-wing aircraft at major airports. ATC will often separate helicopter operations by assigning them altitudes and tracks that “avoid the flow of fixed-wing aircraft”

For example, a helicopter might be instructed to remain below 500 or 1,000 ft AGL when transiting near runway approach paths, so that it stays beneath arriving/departing jets. Helicopters can utilize their ability to fly steep approaches or hover-taxi to stay clear of runways. According to FAA guidance (which is analogous to ICAO practices), “insofar as possible, helicopter operations will be instructed to avoid the flow of fixed-wing aircraft to minimize overall delays,” using closer-in patterns or opposite-direction circuits when appropriate

They may fly a parallel but separate pattern on the opposite side of a runway or make direct approaches to the heliport, depending on wind and traffic

Ultimately, the tower controller is responsible for sequencing and separating helicopters from other traffic, using both horizontal separation (different flight paths) and vertical separation (different altitudes) as needed.

Direct To/From Heliport Operations: Unlike fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters do not necessarily need to use the runway for takeoff or landing. ATC can clear a helicopter to depart from or land at a specific off-airfield site within the ATZ (such as a heliport or even an apron or taxiway at the airport) as long as it’s safe. The FAA’s guidance notes that helicopters may be cleared to take off or land from non-runway areas, including off-airport locations, at the controller’s discretion.

European ATC units follow similar principles. For example, a helicopter lifting from the Crowne Plaza Heliport near Heathrow will be given a departure instruction (e.g. “after departure, remain below 1000 feet and route north of the field”) and only allowed to enter Heathrow’s airspace when it will not conflict with runway traffic. Departures and arrivals can often be timed between fixed-wing movements or routed to a less-used sector of the airspace.

Examples of ATC Integration: At Heathrow, helicopters from nearby pads are typically handed by Heathrow Radar before entering the zone. For the Ascot event heliport, Heathrow ATC requires all operations to follow a specific arrival/departure route and altitude profile within the CTR

ATC provides the local QFE (altimeter setting) so the helicopter can operate at known heights above ground

After departure, helicopters heading south are promptly transferred to a neighboring approach controller (e.g. Farnborough Radar) to clear Heathrow airspace

This ensures the helicopter is under positive control through its entire transit of the ATZ.

In summary, ATC manages heliport traffic by issuing clearances that keep helicopters clear of primary traffic flows, using dedicated routes, altitudes, and timing to maintain safe separation. Controllers and pilots work closely – the pilot must adhere strictly to the clearance (and can slow down or hold if necessary), while the controller sequences the helicopter much like any other aircraft, with adjustments recognizing the helicopter’s flexibility.

4. Regulatory Framework (ICAO & EASA) for Helicopter Operations in an ATZ

Helicopter operations in the vicinity of airports are governed by international rules (ICAO) as implemented by European regulations (EASA and national authorities). These rules provide the legal and procedural framework to ensure safety within ATZ airspace.

Aerodrome Traffic Zone Regulations: The concept of an ATZ is recognized by both ICAO (in guidance documents) and EASA’s Standardised European Rules of the Air (SERA). SERA (Regulation (EU) No. 923/2012) defines an ATZ in the same terms as ICAO: “an airspace of defined dimensions established around an aerodrome for the protection of aerodrome traffic”

Under SERA and national rules, aircraft (including helicopters) must not fly within an active ATZ without complying with specific requirements. Typically, for a controlled aerodrome’s ATZ, this means establishing two-way radio contact and obtaining ATC permission prior to entry or operation. For example, the UK Rules of the Air (which align with SERA) mandate that an aircraft must not take off, land, or transit an ATZ of an airport with an active control tower unless it has permission from ATC and maintains continuous communication

Similar rules apply across Europe via SERA: essentially, helicopters operating in an ATZ with an operative control service must follow ATC instructions, or if at an uncontrolled aerodrome’s ATZ, must monitor the aerodrome frequency and announce intentions.

Airspace Classes and VFR/SVFR: Controlled airspace around major airports is usually Class D or Class C (in some cases Class A in older schemes). In Class D airspace (common for control zones/ATZ in Europe), VFR flights are permitted but must follow ATC clearances and are given traffic information (although ATC separates them from IFR flights if necessary). ICAO Annex 11 and SERA require that ATC provide separation between special VFR flights and between SVFR and IFR flights in a control zone.

Helicopters often make use of Special VFR (SVFR) to operate in marginal conditions within control zones. SERA.5010 details the conditions for SVFR in control zones: SVFR flights require ATC clearance and certain minimum weather conditions. Importantly, the rules allow more flexibility for helicopters. While a fixed-wing SVFR flight requires minimum ground visibility of 1500 m, a helicopter may be permitted SVFR with visibility down to 800 m (provided it can remain clear of clouds and at low speed)

This is an important regulatory difference acknowledging helicopters’ ability to maneuver safely at lower speeds and visibilities. For instance, ATC can issue a SVFR clearance for a medical helicopter to depart the CTR in visibility below 1500 m, as low as 800 m, which is forbidden for airplanes in the same situation.

Furthermore, SVFR is generally limited to daylight operations in most countries (unless special authority is given) and requires cloud ceiling not below 600 ft

These conditions are built into both ICAO and EASA rules to ensure that even when weather is marginal, a helicopter can safely navigate visually within the ATZ.

IFR Helicopter Operations (PinS Procedures): Helicopters can also operate under Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) to heliports in or near controlled airspace. ICAO’s PANS-OPS and EASA instrument procedure design rules include Point-in-Space (PinS) approaches and departures, which are instrument procedures designed for helicopters to or from a point near a heliport. Under a PinS approach, a helicopter can fly an IFR approach to a defined point (often several miles from the heliport or at a safe altitude), then proceed visually to land. This allows integration of helicopter IFR flights into busy airspace by treating most of the flight like a conventional IFR arrival, then switching to VFR for the final segment. Eurocontrol has published guidance on helicopter PinS operations, emphasizing that deployment of such procedures in controlled airspace requires a safety assessment and coordination with all stakeholders

The regulatory framework (ICAO Doc 8168 and EASA AMC/GM) provides criteria to ensure that PinS routes avoid conflicts with fixed-wing instrument approaches. For example, a PinS departure might stipulate a course that immediately turns the helicopter away from the runway axis and keeps it low or in a specific corridor until clear of the ATZ. National authorities must approve these procedures, but they are increasingly used to facilitate helicopter access to places like hospital heliports near airports in low visibility, without disrupting airport IFR traffic.

Other Relevant ICAO Provisions: According to ICAO Annex 2 (Rules of the Air), when operating in the vicinity of an aerodrome, all aircraft (including helicopters) must conform to or avoid the aerodrome traffic pattern formed by other aircraft

In practice, this means a helicopter in an ATZ should avoid the standard fixed-wing circuit unless integrating by ATC instructions. ICAO Annex 11 (Air Traffic Services) mandates that control zones (CTRs) be established at airports with significant traffic, and that ATC separations or advisories cover all traffic within those zones. Therefore, a helicopter operating in the CTR is subject to the same overall ATC authority as any airplane. ATC must ensure either standard separation (if IFR or SVFR) or at least traffic information and conflict resolution advice (if VFR in class D/E) is provided between the helicopter and other flights.

EASA Air Operations Rules: On the operational side, EASA’s Air Ops regulations (Commission Regulation 965/2012) and related rules impose certain requirements on helicopter flights near aerodromes. For instance, commercial air transport helicopters must follow weather minima and performance (engine-out) constraints when operating near congested areas (which an ATZ of a major airport certainly is). Helicopters flying commercially in an ATZ may need special approval if they are conducting low visibility operations or night operations to a heliport without standard lighting. However, these are operational considerations more than airspace rules. From an airspace perspective, the key regulatory points are: obtain ATC clearance, maintain communication, adhere to VFR/IFR minima (with helicopter-specific relief for SVFR as noted), and comply with any additional local ATZ rules published in the Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP).

In summary, ICAO and EASA regulations do not prohibit helicopter operations within the ATZ of a major airport – rather, they provide the structure to do so safely. As long as the helicopter flights comply with ATC clearances, weather minima, and any local procedures, such operations are lawful and routine. The rules actually include flexibility for helicopters (e.g. reduced visibility minima) to facilitate these operations while maintaining safety margins.

5. Safety and Best Practices for Integrating Helicopters in Controlled Airspace

Operating helicopters within a busy controlled airspace requires adherence to best practices to maintain safety. Below are some of the key measures and lessons learned from international experience:

- Established Helicopter Routes and Holding Points: As seen in London, Paris, and Nice, published helicopter routes (often charted on maps) are extremely useful. These routes typically avoid overflight of critical or sensitive areas (e.g. populated city centers for noise, or final approach corridors for jets) and have defined altitude profiles. Heliports in an ATZ should have departure and arrival procedures that are pre-coordinated with ATC. For example, a heliport might have a standard departure route like “Depart to the north, not above 500 ft until reaching X waypoint.” If a helicopter cannot be immediately cleared into the CTR, having predefined holding points (visual reference points just outside or at the edge of the ATZ) is a best practice so that the helicopter can circle safely until cleared. These procedures are usually published in the AIP or local operating charts for the heliport.

- Altitudinal Segregation: Using different altitudes for helicopters versus fixed-wing traffic is a fundamental tactic. Helicopters are capable of flying low, which often keeps them below the paths of airliners. For instance, a departing airliner will be above 2,000 ft by the airport boundary, whereas a helicopter can be instructed to remain below 1,000 ft until well clear of the runway zone. Vertical separation can thus be maintained. In the control zone, ATC may assign helicopters specific altitudes (or altitude caps) that keep them out of conflict. This practice is reflected in guidance that helicopter traffic patterns can be “much closer and lower” than airplane patternsBy flying a tight, low circuit (or direct in/out approach) on a side of the airport not used by fixed-wing traffic, the helicopter stays in its own layer of airspace. This technique greatly reduces the risk of mid-air conflict and minimizes disruption to the flow of faster aircraft.

- Minimizing Wake Turbulence Risk: Wake turbulence from large aircraft can be dangerous to helicopters, which are smaller and lighter. Best practices to mitigate this include:

-

- Positioning helicopter routes so they do not pass through the vortices of departing or arriving jets (for example, not flying directly behind a departing jet or below the approach path of a landing heavy aircraft within a certain time frame). ATC will often apply wake turbulence separation distances if a helicopter is operating on a runway or approach behind a heavier aircraft. However, when off-runway, lateral or vertical avoidance is used instead of timed separation.

-

- Helicopter pilots and ATC maintain awareness of runway usage; controllers may issue specific caution advisories: e.g., “Caution wake turbulence from departing A330, delay your crossing/approach by 2 minutes.” Many heliports near airports plan their location and routes to naturally avoid wake – e.g., Monaco’s route over the sea keeps helicopters out of the immediate wake zone of Nice’s runway 04/22 approaches.

- Special VFR and Weather Considerations: As mentioned, helicopters can operate SVFR in lower visibility. A best practice is that heliport operators coordinate with ATC to have clear policies on when SVFR will be requested or when operations will pause due to weather. Controllers should be ready to give SVFR clearance with appropriate separation. Pilots should be well-versed in SVFR procedures (e.g. remaining clear of cloud, speed 140 kt or less, etc.)Additionally, if weather drops below minima, helicopters might hold outside until conditions improve or divert – this should be pre-planned. Good communication of weather information (ATIS reports, etc.) to helicopter pilots is important so they know the conditions at the airport/ATZ.

- Training and Familiarization: Pilots operating to heliports in busy airspace must be properly trained in those specific procedures. Many heliport operators conduct mandatory briefings for pilots new to the site. For example, the Ascot event heliport provides a pilot briefing package each year, emphasizing required routes and ATC coordination.ATC personnel also receive training for handling helicopter traffic – including understanding helicopter performance (e.g. a twin-engine helicopter can climb quickly to an assigned altitude, or can hold in one spot if needed). Regular coordination meetings between heliport operators and ATC can iron out any issues (this is done in London via a Helicopter Operations Liaison Committee, for instance).

- Operational Restrictions and Measures: Sometimes restrictions are imposed to enhance safety. For example, in the London CTR certain areas are off-limits to single-engine helicopters (except emergency services) for safety, and there are security-sensitive zones where helicopters must have specific clearance to enter.Noise abatement is also a common concern; best practice is to route helicopters over motorways, rivers, or industrial areas instead of residential neighborhoods when near airports. At some airports, helicopters are asked to operate only during certain hours or to avoid peak rush periods of fixed-wing traffic if possible. Slot systems can be introduced during special events to meter helicopter traffic (as is done at large events like the World Economic Forum in Zurich – where heli slots are assigned to manage demand).

- Use of Technology: Increasingly, technology aids safe integration. Transponders and ADS-B are typically mandated in controlled airspace, so helicopters should be equipped and visible on ATC radar screens. This greatly improves ATC’s ability to monitor and separate traffic. Some heliports use Automatic Terminal Information Service (ATIS) broadcasts to give pilots real-time info on airport operations. Additionally, GPS navigation allows helicopters to precisely follow complex route shapes (even at low level), which helps in adhering to defined corridors. The safety case for PinS IFR procedures includes robust navigation specs and possibly the use of helicopter-specific performance-based navigation (PBN) routes to ensure accurate tracking that avoids fixed-wing lanes.

- Emergency and Contingency Planning: Lastly, best practices involve having contingency plans. If a helicopter experiences a radio failure in a CTR, for example, procedures should exist (usually spelled out in national AIPs) for it to squawk a code and either land as soon as possible or follow a predetermined exit route. Similarly, if a helicopter must abort a landing at the heliport (go-around), there should be a known missed approach or go-around procedure that keeps it clear of the airport’s traffic until re-established under ATC instructions. Coordination with rescue services is also wise – e.g., in case the heliport is within the airport’s fire coverage zone, roles should be defined for who responds to a helicopter incident off-airport but nearby.

By implementing these best practices, airports and heliports have a strong safety record. The key is integration without interference: helicopters benefit from access to the controlled airspace and proximity to the airport, while fixed-wing operations proceed with minimal disruption due to careful segregation and timing. Continual communication, clear procedures, and regulatory compliance form the backbone of safe mixed operations.

6. Application to Athens International Airport (LGAV)

Athens International Airport “Eleftherios Venizelos” (LGAV) currently does not have a public heliport immediately adjacent to it, but the lessons from other airports can be applied to Athens’ context to allow heliports within its ATZ safely. Athens’ ATZ (control zone) extends roughly in a 5 NM radius around the airport (Class D airspace from surface up to the TMA). We propose how helicopter operations within LGAV’s ATZ could be accommodated:

- Potential Heliport Sites: First, identify locations around LGAV within ~3 NM that could host a heliport. These might include areas in Mesogaia (Spata or Koropi areas) where corporate or emergency heliports could be useful. For instance, a heliport could be established in the business park north of the airport or at a hospital in the vicinity. Any site must be evaluated to ensure it does not infringe on obstacle limitation surfaces of LGAV’s runways (per ICAO Annex 14 Volume II, heliport placement must consider nearby aerodrome approach/departure paths). Assuming an appropriate site is chosen with minimal physical obstruction impact, the focus shifts to operational integration.

- Coordination with Athens ATC: Helicopter flights to/from this heliport would operate under the authority of Athens Tower/Approach. The heliport should be required to have two-way radio communication with ATC and possibly be allocated a discrete frequency or share Athens Ground/Tower frequency when in operation. Just as in other cities, all such helicopter operations would need an ATC clearance to depart or enter Athens’ CTR. The Athens ATC unit would treat these flights much like they handle helicopters that occasionally use the main airport (LGAV does handle VIP or military helicopters on its runways/aprons from time to time). Controllers would issue instructions to ensure separation – for example, “Helicopter SX-HXX, cleared to enter Athens control zone via Markopoulo at 500 feet or below, report abeam runway 03R threshold.”

- Designated Routes for LGAV: Athens can establish dedicated VFR helicopter routes in its AIP similar to other major airports. Given the local geography, one route could follow the Attiki Odos (the major ring road) to a point near the heliport, keeping helicopters over a transportation corridor rather than residential areas. Another route might run along the coast (if the heliport is on the coastal side) to keep clear of approach funnels. For example, if a heliport were northwest of the airport, helicopters could be instructed to remain north of the Attica Zoological Park and west of the airport perimeter, thus avoiding overflight of the runways. These routes should have altitude restrictions: perhaps not above 700–800 ft AGL when near the airport, which would keep helis below the glide path of jets (the ILS glideslope at LGAV is around 3° – intercepting around 1500 ft a few NM out, so staying below ~1000 ft near the runway ends would maintain vertical separation). Published helicopter arrival/departure routes can be added to the LGAV Aeronautical Information Publication with clear diagrams.

- Timing and ATC Procedures: Athens’ traffic flows tend to be tidal (busy arrival/departure banks). Helicopter operations can be scheduled or tactically managed to avoid those peak times, or else ATC can fit them into gaps. For instance, between sequences of arriving jets on Runway 03R/21L, a helicopter could be cleared to cross the runway area or depart the heliport with minimal delay. Since helicopters are very maneuverable, ATC could even instruct one to hold hover over a known point (e.g., an empty field or a landmark) if a delay is needed, rather than having to enter a conventional holding pattern. Special VFR can be authorized by HCAA/ATC for these helicopters if Athens is in IMC but conditions for the heli are marginal VMC – Greek regulations (aligned with SERA) would permit Athens Tower to issue SVFR clearance provided ground visibility at LGAV remains ≥1500 m (or ≥800 m for helicopters) and cloud ceiling ≥600 ft.

- Safety Measures for Athens: All the general best practices would be applied. The heliport operator and Athens Airport would need a Letter of Agreement defining responsibilities. Pilots using the heliport should be required to undergo a briefing on Athens CTR procedures. The heliport could have lighting and PAPI (if night ops are anticipated) to assist helicopter pilots in landing precisely without conflicting with airport lighting. Regarding wake turbulence, Athens controllers would ensure that a helicopter does not lift off just as a heavy jet is departing overhead. The helicopter could be instructed to wait for, say, 2 minutes after a heavy departure or to depart immediately before a heavy departs (since a helicopter’s downwash doesn’t significantly affect a heavy). These tactics eliminate wake issues.

- Emergency Coordination: LGAV’s emergency plan can include the heliport. For example, if a helicopter approaching the off-site heliport has a problem, Athens ATC could direct it to divert to the main airport as a safe landing area. The airport’s fire and rescue could respond if needed. Conversely, a serious incident at the heliport (fire or accident) would be communicated to Athens Tower so they can halt nearby movements if necessary. Such integration ensures that safety services are unified.

- Regulatory Compliance: As Greece is under EASA, all the operations would comply with the same international standards described. HCAA would oversee that the heliport itself meets design standards of ICAO Annex 14 Vol II (sufficient clearance, marking, etc.), and that its proximity imposes no undue risk to LGAV operations. Any necessary risk assessment (similar to the Eurocontrol safety case for new PinS procedures) would be carried out to the HCAA’s satisfaction, demonstrating that all hazards (airspace conflicts, communication failure scenarios, etc.) have been addressed with mitigation measures.

In conclusion, there is no fundamental obstacle to safely accommodating helicopter or helipad operations within Athens International Airport’s ATZ. By mirroring the procedures used at other major airports:

- Establishing clear routes and altitude restrictions for helicopters,

- Requiring strict ATC clearance and communication,

- Applying the flexibility allowed by ICAO/EASA rules (such as special VFR for helicopters when needed),

- and coordinating between the heliport operator and Athens ATC, LGAV can ensure that any nearby heliport operates safely and in full compliance with international regulations.

The successful examples across Europe serve as proof: a well-managed heliport in or near a controlled airport zone can enhance transport options (e.g. for tourism, business or medical evacuation) without compromising the safety or efficiency of fixed-wing airline traffic. With proper planning and oversight by HCAA, Athens can join the ranks of airports that integrate rotary-wing and fixed-wing operations in harmony.

Sources:

- Eurocontrol, Helicopter Point-in-Space Operations – Generic Safety Case (2023) – notes the need for multi-stakeholder coordination and safety assessment when implementing helicopter procedures in controlled airspace.

- ICAO/EASA Regulations: SERA.5010 (Special VFR in control zones) – permitting helicopters in CTR with 800 m visibility (vs 1500 m for fixed-wing); Definition of ATZ per SERA/ICAO.

- CAA-UK, London Helicopter Operations – Use of Helicopter Routes in London CTR, highlighting ATC clearance requirements and predetermined helicopter routes.

- FAA AIM (analogue procedures) – guidance that helicopters should avoid fixed-wing traffic flows and can use separate patterns or off-runway landing areas, with ATC maintaining separation.

- Monaco Heliport information – example of routing helicopter traffic over water to minimize noise/conflict with Nice Airport traffic.

- Pooleys Heliport Directory (2023), operational details of heliports near major airports (e.g. Crowne Plaza London Heathrow heliport 1 NM from LHR) and special procedures within Heathrow’s CTR.